A First Row Ticket to Hell

Tapachula, Chiapas Mexico

May – June 2019

What is happening in Central America is the most horrifying thing I have ever seen. I feel like I am looking down into hell watching people climb over each other trying to get out only to have 99% of them thrown back down into the fire. The failure of modern society is undeniable in Tapachula Mexico.

This is one of the last places on the planet that I ever thought I would be. Not because it seemed to be a particularly offensive place, but simply because it was a place that I had never heard of as of three weeks ago. My girlfriend, Anna has much more awareness about these sorts of places. She was the one that got in touch with the human rights group, and she was the one that received the invitation to come volunteer for a short while. I did not protest at all. It seemed like it would at the very least be a very interesting learning experience.

The migration from Central America sits alongside the recent Syrian exodus, and the flight from Venezuela as one of the largest humanitarian crisis’ of the modern era. The reasons for this migration are not quite as clear, but it is no less important. Nothing has done more to define the 2010’s geopolitical environment than the war in Syria. The constant chaos in Venezuela is also front and center to all of those in the developed world. What is happening in Central America is much more complicated, much less appealing to headlines, and much harder to empathize with. The mass exodus from Central American is caused by a variety of factors that bleed slowly over the course of a decade. The ability to see it firsthand is not the most appealing thing in the world, but it is the only way to see the reality.

What we found when we got here shouldn’t have been that surprising, but it really doesn’t hit you until you see it first hand. Every single time we told someone that we were heading to Tapachula they immediately gave us a look of complete shock. That look is always followed by hearing about how ugly it is. Tapachula is like a dirty word in Mexico. It’s not a place most Mexicans expect a gringo and a Spaniard to visit. This Guatemalan border town has become synonymous with what has become one of the largest mass migrations of our time.

The first night we arrived we took a little walk around the town to see what we could find with the intention of using an ATM. The first thing you notice upon arrival is that you have seemingly entered one of the most diverse cities in Mexico. It’ probably also the most diverse city in the world with a population of less than half a million. You expect to see Mexicans, Guatemalans, El Salvadorians, and Hundorans here, but you don’t expect to see Syrians, Sudenese, Haitians, Indians, and Thailandese. Nevertheless, you see people from every corner of the world sitting on the side of the street just waiting for something.

The ones that came here from another land mass tend to be less desperate. They were after all able to afford to fly here. The ones you expect to be here have a particular type of desperation that not many people have the misfortune to experience. It is the level of desperation that makes you willing to walk thousands of kilometers across three of the most dangerous countries in the world in search of an even marginally better life along the way. It’s an experience nobody should ever have, but it is the reality of almost every person I see here.

After exploring the town for a little bit more than an hour we see a crowd of Central Americans gathered around the only open bank we can find. Between 5-10 people wait to open doors for people for even a chance of receiving a peso for the convenience. One after another people step out of the bank and the crowd immediately begins to compete for attention in order to be the one that gets the peso. Inside the bank it’s like a different world. The room is filled with people that are fortunate enough to have a bank account. Most of these people are native Mexicans, and they don’t seem to be too happy about stepping outside.

Upon leaving it’s like walking out into a horror movie. Everybody outside immediately starts yelling towards you at the same time, all with their hands outstretched. Some tug on your shirt sleeves to make sure you know they are there. Never in my life can I remember a specific time that I have gone to an ATM until today. First impressions are important, and this little experience was my first impression of this city. We haven’t even been here for more than 2 hours, and it’s already clear at this point that even some of the most common tasks of the day are going to be different in this city.

The town center is unlike any I have seen in Mexico. A town of this size in Mexico at this time of day will typically have people outside dancing as a live band plays, or stands of people selling corn, tacos, and ice cream. Here the normally lively center is still very alive, but in a different kind of way.

There are migrants from all over the world in nearly every single place they can be. Every single store, and every single corner has a crowd of migrants waiting to beg for money. The amount of people is absolutely inescapable, and it is impossible to look around without catching the eyes of at least one person. This level of poverty is something impossible to imagine in most cities of the world, including other parts of Mexico. They are simply some of the most unfortunate people on the planet. They have no food, no water, and little hope of having either. This is their reality, and I am simply a temporary observer.

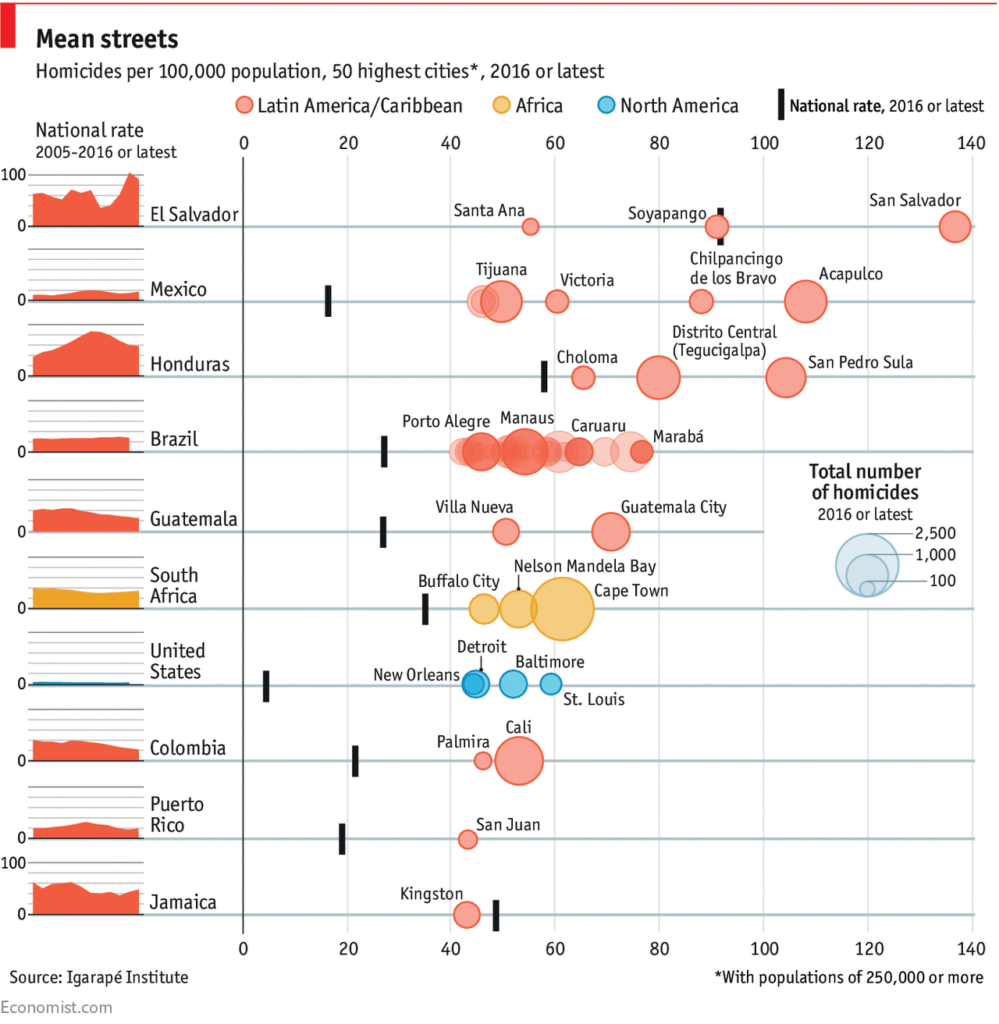

The levels of violence that these people come from is unprecedented in the history of the world. Once you learn what conditions they have dealt with, it becomes easier to understand how they arrived here. Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico have spent the last decade taking turns with having the most dangerous city in the world.

The cities of this region of the world can make medieval Europe look like a utopia. Simply having access to drinking water can make you the target of someone looking to extort a bit of money. Once they ask for more than you can afford then all you can do is leave with your family for the hope of a future life in another place. When you stay you risk having your daughter, mother, sister, or anyone else near you murdered for revenge against your transgressions. They do not kill you, if they did that they wouldn’t have anyone left to extort money from. The gang members of Central America are different types of monsters. The ones fleeing this violence are only one type of migrant though.

One night when walking to the corner market I came across a particularly upsetting case. A girl no older than 20, covered head to toe in chicken pox, stood waiting to open the door for people with her toddler daughter in hand. I do not know her story, but based on what I have learned I can speculate. There is a certain migrant archetype that is incredibly common, and chances are that this girl fits that. Young girls in gang controlled land are coerced or traded into relationships with gang members. The relations they are forced into are often times unbearable. As soon as the abuse gets too much the women need to leave. Staying is a death sentence, so they do the only practical thing they can do. They take their children, and start the incredibly dangerous months long walk to The United States.

An estimated 80% of the woman taking the migration are subject to some sort of sexual abuse. Somewhere around 60% of all migrant women are raped along the way. They have become so accustomed to this abuse that the migrant community has turned birth control into a basic need. Nearly every woman heading to the US is warned to have a birth control plan for the journey. It has become so bad that priests in Mexico have started opening clinics to provide birth control injections to migrants. They are doing something completely opposed to their faith. To them it has become a simple choice between the lesser of two evils.

Tapachula is a relatively safe haven on this trail where migrants can stay to gather their thoughts before making their way through the length of Mexico. It’s kind of like when you were a kid and you played the game “the floor is lava”. In this case Rural Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador are lava, and Tapachula is one of the chairs slowly sinking into the lava. The human rights groups have created a small safe place to await refugee status. Without them, there would be very little hope in this town.

Tons of young mothers make an effort to obtain refugee status in this city in order to avoid this journey. The streets are filled with toddlers who should be sitting safely at home watching the latest disney movie. Instead they spend their days helping their mothers beg for money, so they can eat. When the hearing is almost inevitably denied, they then have no choice, but to follow their mothers further on. It’s about 9,000 kilometers to the US on the back of La Bestía, the most dangerous train in the world. For the wives of gang members it’s a trade between possible death, and certain death. The choice is obvious.

The chance that anyone ever receives refugee status here is about 1 in 20. The international refugee programs were created for a different time. The people who wrote those laws assumed the people applying would be fleeing something like a Nazi concentration camp. They assumed that the case would be obvious. The laws were written in a way that allows countries to shuffle around the responsibility of taking people out of pure speculation of it that person is in provable danger. The people applying need to practically call the people trying to murder them before anyone in the immigration departments begin to take their claim seriously.

Luckily for those trying to prove their status in Tapachula, the same people trying to murder them often end up waiting in the same immigration lines. It makes it really easy for the hunted to prove they are being hunted. Everyday there is a crowd of at least 100 people standing outside the local human rights organizations. The crowd is always full of the hunted, the hunters, the innocent, and the guilty. They are all there at the center for the same reason, although they may have found themselves there for different reasons.

The ones who are escaping the gangs have many reasons to run, but they are not the only ones who have been forced into their current circumstances. It’s not just the pure victims of the situation that suffer. The oppressors are often in their own situations due to unmitigated circumstances that pushed them into this life at a very young age. They come from a place where often your only choice is to join the gang. The only chance a lot of them were ever given was join the gang or face an early death.

The poverty in the countries they come from is incredible, and that is not even taking into consideration that El Salvador, Southern Guatemala and most of Honduras have been in a drought for the last 10 years. Agriculture is being destroyed by a one two punch of corporate farming and climate change. Corporate farming has prioritized almost all of the land to cash crops which puts all of the wealth of the country into foreign corporations, and the local politicians they lobby. Sugar cane has sucked the nutrients from the soil, and the decade of drought has made the land almost worthless.

The rural areas of this part of the world often go months without running water, particularly in Honduras and El Salvador. Even in the well kept house where we are staying, we are lucky to have running water more than an hour a day. The water went out the week before we arrived, and no one seems to know when it will come back. Even so, the conditions we have are pretty high compared to the rest of the town. Anna has started to volunteer at the human rights center, and the stories that we begin to hear are nothing short of disturbing.

One of the first stories she hears is of a group of 30 to 60 Cubans who had been locked in a room built for four people for around 2 months. The only reason they ever got out was due to the human rights center taking on the case for free. The government here is perfectly happy to commit human rights abuses without recourse. If it wasn’t for the human rights centers here, they would get away with torture without recourse. That was only the first of many horrible stories she told me. There was one particularly awful story she told me near the beginning of our second week.

One of the lawyers at the center had been working on a case for a young mother who was attempting to receive asylum in Mexico. The woman was fleeing gang violence from Honduras with her 18 month old daughter. The authorities removed her daughter from her once she entered the Tapachula detention center. The refugee application process typically takes three months, and having a lawyer help you through the process is essential. Unfortunately, someone from the government had a personal vendetta against the lawyer that was helping. The government had already separated the family for some time. The official was able to conveniently claim that the mother was incapable of caring for the child. The 18 month old child ended up deported back to Honduras alone while the mother stayed in detention awaiting her asylum trial. Stories like these are everyday occurrences for those trying to help migrants.

Around the Table

At our home, we also have the opportunity to view the migrants from a Mexican’s perspective. Every single day there is an article in the paper about the triumph of the state. It always starts a conversation between Sayyid, the keeper of the house, and the owner, his elderly mother. His mother has a pretty typical view of migration that you would expect from someone her age. They don’t have very much sympathy for the people occupying their town. That is especially true for the people who made their way here from India.

It probably doesn’t help her point of view when she lives next to a slum filled with about 60 people from India. She always likes to remanence on what the town used to be like before the Indians, Africans, or Central Americans showed up. She always says how peaceful everything was in this little port town near the ocean. Nothing out of the ordinary ever happened here before.

40 years later, the neighborhood has transformed into a series of slums for the displaced with a handful of holdout natives. Who knows what the neighbor of this house used to be like. Now some slumlord has moved in to take advantage of the situation. The entire building has been lined with beds, so that as many high paying Indians as possible can have a bed. When they run out of those beds then there is always enough room for people on the floor. None of these people are much more than skin and bones, so it’s not too hard to play human tetris.

Every single space in the three story building is used to keep people. The only remaining space, the third floor roof, is designated as the laundry area. The people here have learned pretty clearly to respect the boundaries between people. The Indians have a pretty clear understanding that not too many people here want anything to do with them. They only ever talk to us on the occasions where they accidentally drop their clothes into our yard, and then the conversation is very brief.

It wasn’t until the beginning of our third week here that one of them spoke more than five words to us. The conversation started the same way as every exchange, with me helping him get his shirt out of our yard. I happened to be going out at the same time to find some cold remedies for Anna, which made our timing impeccable.

The guy was immediately different. Every time someone asks us to retrieve something it is always a different person physically picking it up. This guy made it a point to come down to greet me, and he is incredibly eager to practice his English.

The conversation starts with the typical small talk. He tells me a little bit about his home town near Delhi, and I tell him a bit about mine. He tells me that he is 19 years old, and I learn that he learned English in secondary school, but he has not had a lot of chances to practice. Nevertheless, his English is very good, so I make sure to let him know. He thanks me for the compliment, and tells me that he has to go finish his laundry.

“If you ever see me sitting outside feel free to shout down to me, and we can chat a little bit more.”

“I would really like that”

“Well I have to run to the pharmacy now, so I will talk to you later.”

I left going one way, and he left going another way. I had a mission to go and find some ginger and hot tea, but I really didn’t know if I was going to be able to. Finding even basic supplies in this town can be a lot harder than you may imagine. The first place I stopped at only had bottles of iced fuze tea. Luckily we are only a block away from the middle eastern street.

This street is the area where just about every person from the middle east or africa hangs out. It is lined with stores and restaurants from that part of the world. It’s like walking into another country. There are certainly a lot of problems that have come from the economic challenges of the influx of people. This change has also made the city incredibly diverse. Over time, as the people here integrate into the culture of the city, this street will likely prosper, and a new subculture will be established.

That potential future is still just that though. If things go well here then a better future is a real possibility, but who knows if it will happen. For the time being, this is one of the roughest places in the city. Whole families from Haiti and the middle east are just sitting on street corners. The mothers desperately try to entertain their children. As soon as I enter the street, I have an eerie feeling of being watched.

It may not be the safest place to be, but it is the only place in town that I can imagine having ginger or hot tea. The second shop that I stopped in was a little middle eastern market with a very friendly looking man. I quickly explain what I am looking for. He tells me that the best place to look would be the oxxo I just came from. My luck does not seem to be very good so far, but I am also not one to be easily dissuaded. I decided to simply go deeper into the neighborhood, and see what I could find.

Not long after leaving the shop I noticed a really unnourished Central American catch my eye as I walked by him. White people are not a rare thing in Mexico, but they are certainly rare in the refugee communities. On this street I stand out like a sore thumb, and that young guy has now started following me trying to get a good angle to my back pocket.

Luckily exactly what I was looking for came into view almost immediately afterwards. A very nice shop filled with fresh vegetables, and all sorts of uncommon oddities for this city. The checkout counter with the clerk is not very far from the door, so I take the opportunity to turn around and ask my new found shadow how he is doing today. The look on his face is something between apathy and fear. Not a sort of fear of getting caught, but a sort of desperation.

He wasn’t trying to pick my pocket, because he wanted to buy some nonsense. Instead, he was trying to pick my pocket so he could eat today. Most of the people in this city are simply waiting to hear about their refugee application. Between the time they apply, and when they get the result they have three months where they cannot legally work. This is the refugee limbo. This guy had gotten so used to pick pocketing people that when he was caught he didn’t even blink an eye. As soon as I turned to talk to the shopkeep he went ahead and even tried to do it again.

I certainly cannot blame him. If I was in his situation I am almost certain that I would do the same thing. When you are desperate to eat, you never know what sort of things you would do. Nevertheless, it is not so great to be on the receiving end of it. The shopkeep told me once again that they did not have anything that I was looking for, so I decided that it was time to end the adventure.

Out of the store, the pickpocket was still following me closely behind. I quickly cut in front of a car, and into a crowd of people. The risk of getting hit by a car prevented him from continuing to follow me. A few minutes later I am back on our quiet little street trying to get in as fast as possible, happy to leave the outside world behind for a bit.

A couple hours went by, the sun set, and then out of the darkness I hear someone yelling my name. Looking up to the next door roof there I see my new friend alone yelling to try and get my attention.

“Bryce, are you there? I wanted to talk to you.”

“Why don’t you come on down, and I will meet you outside the door.”

The conversation starts with the same pleasantries. He tells me about his day. I tell him about Anna, and about her being sick. He confirms my suspicions about the conditions next door, and then he starts telling me his story.

His life is something that I have no chance to relate to, so I immediately find it hard to carry on any meaningful conversation without reverting to a simple interview. He starts by telling me how he got here.

“On March 28th my parents gave me $2,000 and I flew to Panama”

That didn’t really seem to answer too many questions. All I could do is ask more questions. “Why did you fly to Panama? When was the last time you spoke to your parents? How did you get here?”

“I last talked to my parents when I left my country. They sent me to Panama. There was a threat on my life by the Mafia, and it was easy for me to get into Panama. I walked here, because the mafia robbed me in Panama city, and I could not afford anything.”

“How long are you going to be here?”

“I got here a week ago, and have a few more days here. I am hoping to get enough money together to go to Mexico City. Then I am heading to the border.”

Just in those few sentences there is a whole lifetime of stories that I know I will never be able to understand. My most pressing concern on March 28th was speculating over what would happen in Avengers. I was in Querétaro, one of the wealthiest cities in the country, a city that may as well be in another country. The only sign of any of this reality there was the knowledge that La Bestía ran by the outskirts of the town, and the occasional Guatemalan that would walk up to our dining room window begging for money. At this moment Querétaro felt like a lifetime ago.

“What is your plan once you get to the border?”

“I go in, and I do this.” He says putting his hands up in a gesture of surrender. “I will give myself to the authorities.”

That alone speaks volumes to me. All I hear in US media is how the refugee camps are the worst thing that has happened since slavery. Here is someone telling me that he is going to spend the next month of his life moving 9,000 KM through gang infested jungles and deserts for the privilege to spend some time inside of a US border camp.

“I am sorry, but my English is not so good.” He continues, self consciously. “Do you have water right now?”

“Yeah, give me a minute”

I quickly went through the gate trying to not keep him waiting too long, and headed back to our room. After what happened a few hours ago, I don’t really feel like walking around with my wallet and phone, especially now that the sun is down.

“I am heading out for a bit” I told Anna when I got into the room.

“Really? Now?” It was already 9:30 pm. The town generally did not feel very safe in the middle of the day, let alone at this time.

“Yeah, I’ve been chatting with one of the guys next door. I am going to go on a quick walk with him, he seems nice enough. He is the first person from that house that has approached me beyond asking for their clothes back.” For the last two weeks I had grown increasingly interested in what the story was with their situation. “I won’t be long, and I am going to leave my wallet and phone here just in case.”

I left the room, and began looking around for anything that we possibly had that I could give him. Our water supply had dropped to just one liter until tomorrow. As much as I wanted to help the guy, I wasn’t going to give him our last bit of water, especially while Anna was sick. I glanced around the table to see what else we may have. I only found a bag of bakery I had picked up earlier in the day with a few pieces left.

A moment later I was on my way back out to greet him with the bag of bakery in hand. He had not moved since I had gone back inside. “Let’s go on a walk around the block. It’s late, and this isn’t our house, so I can’t really invite people in.” I wanted to let him sit down, and have a bit of bread, but I knew that the owner of the house would not be too happy about that once she found out.

“Where would you like to go?”

“Well why don’t we head that way?” I said pointing towards the main square, as I began pulling out a pretzel roll from the bag in my hand. “Here, I got you some bread. Unfortunately, we don’t have too much water, but I was able to grab a bit of bakery for you to have.”

“Have a bit.” He said pulling off a third of the roll and handing it to me.

This quickly followed with a brief argument with me insisting that it was all for him, and him refusing to eat any of it unless I had some with him. “Alright, alright,” I said “You win.”

He handed me the piece he pulled off, and we were off. He had the unintentional figure of a mildly anorexic supermodel. The pretzel was gone before we made it to the corner of our street where the regular rough looking crowd of people had gathered for the night. I wanted to stop by a corner store, but I was not keen on going where the gangs congregated through the night. I lead us right past them, and onto the next street.

“Here try this roll. They are not too bad.”

“Does it have any meat?”

“Nope, it should be fine for you. I think it is only a bit of air inside. You are Hindu correct?”

“Yes, I don’t eat beef.”

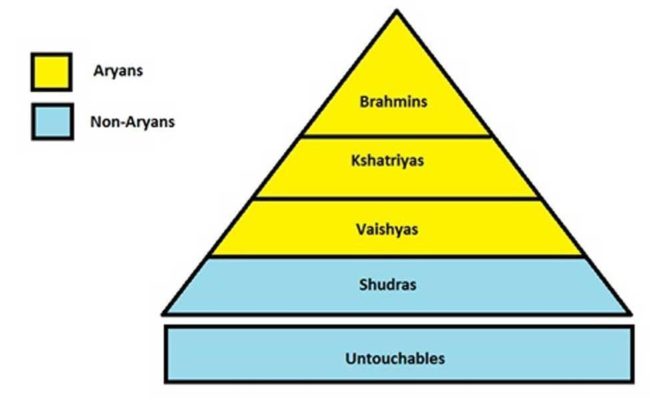

Him being a Hindu seems like a bit obvious being from India and all, but you never know. He could have just as easily been Muslim. It seems trivial, but the religion of someone from India will tell a completely different story as to how they ended up in this situation. I know enough about the social conditions of India from Anna’s experience of working with untouchable Indian prostitutes to know that a lot of people born there have their futures carved in stone the moment they leave the whom. I can’t help but wonder what caste he was born into to have reached this moment in his life.

Just around the corner he sees someone across the street, and waves them over to give them half of the piece of bread. Once the guy comes over, I immediately recognize him as one of the homeless Central Americans that is always sitting by the main square. “He helped me yesterday, so I try to help him today.”

“I see him around a bit, but I have never really talked to him. Is he a nice guy?”

“Yes, he tries to help anybody he can.”

“Well that is good to hear. I am glad to know that people are helping each other.” The market around the corner is much less busy, so we head on in to see what they have. Right in the center there is a tower of two liter water bottles for 18 peso a pair. “Here I am going to get you a couple of water bottles.”

“No no no,” he immediately pulled them out of my hands, and put them back where they came from.

“Please, I insist. It really is no bother to me.” I grabbed the same two bottled, and he immediately put them back down. We repeat the cycle three more times until I relent. We left the store without a purchase, and make it the last couple blocks to the main square. “Why did you decide to come here?”

“The mafia was after me, so my parents sent me here.”

“I guess what I mean is, why the United States? Why Panama? Why not Singapore, or Thailand?”

“The US is far enough away for me to be safe, and it was easy for me to get into Panama. Then I could walk.”

“Do you ever think about just staying here?”

“I would not. I am not safe here. They do not want us here.”

It’s hard for me to say much more after that. I wonder if he is aware of how unwanted he is in the United States. It seems to me that he is at least partially aware of how migrants are treated these days. He is knowingly walking to the United States where he will immediately enter a detention center while the US government debates what to do with him. Right now though, after spending the last month being treated like a walking piece of shit, I think he really just wants someone to treat him like a human. Unfortunately, I do not even know where to start when it comes to relating to his situation. “Well I hope you make it alright.”

At that point I start to notice all of the migrants sitting in the square staring at us. We are starting to push towards 11 pm. The sight of a US citizen talking with an Indian migrant is an uncommon one at 11 am, let alone 11 pm. The sudden awareness of the eyes on us, and the realization that everything has finally closed for the night causes a sudden wave of unease. This is not my reality, and I am the odd one out here.

“Why don’t we head back, I am starting to get a bit tired.” With that we left the square, and head back towards the corner shop on our block as I try to come up with anything meaningful to say. I cannot help but fall back into trying to understand his situation. Somehow, inquiring about the Avenges just does not seem appropriate. “How did you get into Mexico?”

“I was able to get some fake papers. They took my real passport in Panama, but the mafia got me a fake.”

“That may actually help you in the US. If they cannot find a place to deport you then you may have a higher chance of staying.” The corner shop came into view just then, now accompanied by a large crowd of Indian migrants. “How long do you think it will take?”

“It doesn’t matter. It will be better for me either way.” He waved towards the Indians, and turned to me one last time for the night. “I am going to stay here.”

“Tomorrow if you see me shout down from the roof, and we can talk some more. Have a good night.”

With that I quickly headed back to the house, and began to wrap up some remaining work. The nightly rain started shortly afterwards, so I enthusiastically collected a couple buckets of water for my morning shower. Once the rain finally finished around 2 am I went out to dump the newly collected water into the tank, and noticed that someone had come out to the laundry area next door.

I could not make out much of who it was, or what they were doing. They were talking just loud enough for me to hear a bit of Hindi rhythmically come over the sound of another raid in the main square. Even within the refugees there are those who are far more fortunate than others. The men from India can safely sleep without worry about where they are going to go during a torrent. They don’t have to worry about being awoken by a Mexican military officer ordering them to get into a truck to be taken off to an unknown location.

The next day was a slow start with a quick walk to one of the many Chinese restaurants that have resulted from the last wave of migration. Then back to the house to see if my new friend is going to show up. The house is completely empty now besides Anna sleeping off her sickness in the other room. It is the best time to try and concentrate in an environment that seems obsessed with testing my mental fortitude.

That moment of silence does not want to last though. It does not take long for the main door to open up, and Sayyid’s car to pull in with his mother in the passenger seat. I guess my concentration is going to have to wait a little bit. They are both very nice company, and Sayyid has done a ton of work with the community here to try to make things better. It’s always a pleasure to talk with him, and I have so many questions after my conversation last night.

The next moment I looked up, I saw my new friend walking right past the passenger side of the car, enthusiastically trying to get my attention. As understanding as Sayyid is about the current situation, I know this is not a trait his mother necessarily shares. The look on her face as my new friend walks by her car door only serves to confirm this thought. Sensing that some sort of catastrophe was upon our small house, I quickly leapt to the door in order to catch him before the mother freaked out due to someone that she clearly did not like walking into her home.

“Hey! How are you doing today?” I called towards him.

“Hello, are you busy right now?” he enthusiastically replied, oblivious to the looks the mother was shooting in his direction.

“Well not too much, do you want to go for a walk?”

“Can we sit here and talk a bit?”

“Unfortunately, this isn’t my home, so I can’t really invite people here. Why don’t we go get some food?”

“I am not really hungry, and I was hoping we could stay somewhere.”

I quickly tried to come up with the softest way to let him know that staying here was not going to be a good idea without telling him that the owner of the house would not be too welcoming to him. If he knew that then I am sure he would understand. I could not imagine being in his position, but I can imagine that being in the house of someone who despises you is certainly not a place that you want to be even in desperate situations.

“Well, the thing is that the owner of the house really doesn’t like guests, and it probably wouldn’t be a good idea for us to stay here.” With that he took a look over to the car where the mother was currently grabbing her walker as she made her way out of her carseat. I truly thought that I had safely prevented a potential disaster. That would have been correct if it wouldn’t have been for the look currently adorning the mother’s face. The two of them were staring right at each other, and the mother had the most grotesque look of disgust that I had ever seen in my life.

“Oh, ok,” was all he said after locking eyes with her, and quickly darted back to his building.

“Shout down from the roof later tonight, and we will go do something then.” I yelled after him, but he was pretty well gone before I could even start talking.

He did not show up for the rest of the day. I took a walk outside to see if I could come across him, but there were no signs. The next day I went out, and right when I got to the southern corner of the block I saw him waving to me from around the corner.

“How are you today.” he asked with a slightly tired tone, but still relatively cheerful.

“I’m doing pretty well. Just taking the laundry to the wash. Why don’t you come along?”

“Just for a little while, I need to go home soon.”

“I am very sorry about what happened yesterday. The person that owns the place we are staying can be a bit unpleasant sometimes.”

“Does she think I am a criminal?”

“No, she is just afraid of what has been happening to her town. When she grew up, it was a very small town where nothing exciting ever happened. Now all of a sudden there are people from Sudan, India, Syria, Haiti, Cuba, El Salvador, and Honduras everywhere. A lot of people don’t like how much it is changing, and they are afraid of this change.”

He looked at me in a sort of somber way as if he hadn’t really thought about what this town was like before the influx of migrants. It is honestly pretty hard to imagine this town without a crowd of Haitians sitting on the street corner. The whole image of the town has become one of a migrant hub. It will probably never again be that once quaint Mexican town that our host still has within her mind.

“Think about it like this. What if one day a quarter of your town were people from the United States, and what if it all happened within a couple years? People would probably not like it too much.”

“Yeah, I guess”

“Don’t think too much about it. The world is changing very quickly, and most people are just not ready for it yet.”

“Well I need to go home.”

“Sounds good, and remember if you ever want to talk about anything just shout down to me, and I can meet you outside.”

After talking with him I felt a little better about the whole situation, but still not perfect. Both of us only had a few days left in the city. Finding a way to get in touch with someone in a city like this where the social lines are so clearly drawn to keep people apart, is understandably hard. This is especially true when the person in question does not have the financial means to own a phone. I hoped to have a chance to see him again, but I started to get the feeling that our social lines had been reestablished.

This whole experience was beginning to be very draining, and isolating. It doesn’t help that this situation has become nothing more than a political talking point back home. Every time I jump online I see people back home talking about what is happening from one point of view or another. People in the US seem to have two perspectives about all of this. Either they believe everyone coming across the border are villains that need to be kept out at all cost, or they believe that everyone should be let in without any sort of process. One side comes from a point of fear. The other side comes from a point of compassion. The nuances of reality have for the most part been completely ignored. The people between these two extremes have been almost entirely silenced.

Those that have chosen to disregard all migrants as villains have not taken the time to accept the responsibility that US citizens have for this situation. US intervention in the region, and constant deportations of actual criminals back to Central America are the seeds of instability. You can’t spend 50 years overthrowing governments, supporting genocide, and dictating another government’s national policy, and then act like what is happening there is not your responsibility. These people love to take credit for when things go well in a nation the US has intervened in. As soon as things go wrong, they are nowhere to be found. Their entire point of view is nothing more than nationalist paranoia, and entertaining this perspective is for the most part a giant waste of time.

On the other side of the argument there are all of the people that have taken the moral high ground. They demand the closure of border camps immediately without thought of what happens next. You must think about what happens when you let a million people walk into the United States without legal status. Most of the migrants are completely unaware that the legal refugee process takes more than three months to complete. That makes a million people with nowhere to go, and nowhere to work for three months while they simply wait just like all of the people sitting on the streets here.

The US camps in their present form are certainly a thing to invoke disgust, but closing them is not compassionate. Without refugee camps then you are going to have another crisis on the streets of the United States. Almost a million more people a year begging for money with quickly degrading health. It would be like when Reagan closed the mental hospitals all over again. Any real solutions will require real and honest discussion between people, but we seem to be past the time of civility.

No matter who I try to talk to in the United States I cannot find a single person that will simply discuss what is happening. Every single person has dug in their heals into one of these points of view. The reality of most situations is almost always in the middle of the extremes. In a country of extremes, trying to look for reality has almost become more offensive than anything. If people can’t fit a point of view into a predefined box of perception then they don’t know what to do with it. Free thought has been completely replaced by an unbelievable sense of mob rule. Not a single person I know has spent time pursuing first hand knowledge of the situation. Regardless, people fill my social media feed with broad proclamations of what is happening, and what should be done.

I feel more isolated from the place where I was born than I ever have. All I want is to be able to discuss with someone without them constantly regurgitating politics they heard from Vox or Fox. People are most dangerous when they feel enlightened to what they perceive to be the truth. It was this sort of truth that caused the death of half a million Iraqi’s, and caused Kennedy to come within minutes of starting World War III over a misguided invasion of Cuba.

Luckily one of the few people in the world that I know who truly understands the power of propaganda emailed me two days after I last said bye to my new friend from India. He has just recently finished his move from Changsha to Shanghai, and he is very eager to simply hear about what is happening here, and very eager to show me his new reality.

The Chinese government has done a good job of isolating its citizens, so unfortunately email has become one of the only ways we can keep in touch. Every time I do hear from him I can’t help but feel happy to know that I have a friend like him. It’s a bit ironic, but one of the only people that I feel like I can discuss the world with is someone who is from a nation, which my own nation seems to be currently starting a new Cold War with.

We share a very similar point of view about what is going on here. This is a bad situation, and that is really all there is to it. There is no simple solution to what is happening here. The only thing that is going to fix this in the long run are fundamental changes to society that no one is willing nor ready to even approach. Until that happens, people are just going to continue to ignore the responsibility that every person on this planet has for everyone else. In the meantime these people will suffer more than anyone else. US citizens will continue with nonsense arguments about the moral thing to do as if the nation responsible for more deaths on this planet than any single country since the Chinese cultural revolution has any merit to speak of morals.

For the most part, people in the US do not want to close the camps, due to feeling responsible for the suffering of those people. Instead, their motivation comes from the same nationalism as those who outright deny the migrants knocking on the door. They are simply ashamed to be from a nation that commits visible crimes against humanity. They act as if the last 50 years of history have just skated by them without much of any consequence. If those taking the high ground really cared about the moral thing to do then there should have been protests in the street when the Obama administration overthrew the Libyan government, and threw that nation into a decade of civil war.

I don’t buy anything that a US citizen says in the matter. It’s all just politics to protect the identity of “American”. It’s just an engineered line of reasoning handed down from some corporate entity working to protect their own interests by making their consumers feel enlightened. I am so very lucky for my friend Corbing. At least in China, people know they are being lied to. An illusion of freedom is a strong ally for those hoping to keep people where they belong.

The next day Anna was feeling better enough to go back to volunteering. I took the opportunity to take a walk out of the city center. It does not take much to get into what is essentially a completely different city. The very center is filled with migrants. A little bit further north you find the human rights center nestled into the outskirts of the migrant epicenter.

When you keep going beyond that, the appearance of the migrants completely disappears. There you will find nice cafes, restaurants, and everything else that you would expect to find in any moderately affluent neighborhood. That is where I find myself today. I found a nice little cafe where I can sit down and write hoping that nothing exciting happens for the day.

Again, that hope does not last too long. It does not take long for a bunch of messages to start coming in. A surprise caravan of 800 had shown up at the border today, and were in the process of making their way to Tapachula. Just about every single person at the human rights center had gone out to observe the caravan. A very common practice that tries to help make sure that there are no human rights abuses by giving witness to said abuses.

The day is pretty typical with a rough temperature of 40c and 90% humidity. Not great weather for a 30 KM walk along a highway, but any day is as good as any to make the journey to Tapachula. The caravan started pretty typically. All 800 of those people entered Mexico legally and unopposed. The human rights group began tweeting immediately as they sat by watching in nearby SUVs.

An hour into the walk, and more news comes through from the twitter feed. A massive caravan of busses had arrived to detain the entire caravan. After making it a fifth of the way to Tapachula every single person from that caravan was rounded up. They were taken to one of the many stadiums and schools that have been converted to detention centers. What is the explanation for this? If they were going to arrest them all anyways, why were they allowed to legally enter Mexico, spend an hour walking in dangerous conditions, only to be arrested later?

It seemed like the whole thing was done to make a point to the migrant community. The whole caravan was processed, and isolated for five days. Once they were freed they were all given a choice. The choice was between going back to Guatemala, or receive their temporary stay so they could pursue their options beyond that day. Out of the 800 people that entered that day five chose to stay. 795 people decided that they were better off turning around. What happened to those people from the moment they were arrested until they were released is simply a mystery.

The next few days, Anna had been spending all of her time at the human rights center, and I thought it may be worthwhile to stop by for a visit. The building has a large steel door with an intercom system. Every person needs to buzz the intercom so someone can conduct a quick investigation before they are let inside. Once inside it is like you have passed the gates of a prison, but in reverse with the security designed to keep prying eyes out.

Inside there is a giant beautiful mural on the wall and about 100 migrants jammed into the main room. There is a feeling of hope and life here. Lively discussions are happening, and the people have a vivacity unlike anyone you will find in the streets. The offices of the building are small with all available space designated to fit more migrants. There are toys for the children, and legal advice for the adults. Everything here is organized to make everyone’s experience as comfortable as it possibly can be.

Between stepping into the main offices, and stepping out, the classroom off to the side was filled. Now every single person eagerly listens to the lecture. The people running this center are doing all they can to help the migrants, but there is only so much they can do. The topic of the day is teaching the migrants what sort of options they have. They have already made it quite a ways, but they have a long arduous road ahead of them no matter where they end up. A lot of them will finish the journey in a body bag, and a select few will be lucky enough to have a happy ending to their story. The most likely end will be something in between.

While they listen to the advice given to them their children wait playing with the many toys in the main room. The absolute innocent of the situation will need to wait for their parents to make a decision for them. They are caught in the middle of something they cannot control. The simple victims of international politics go on, and move on with the little control they have over their own lives.

The people at this center are fighting an uphill battle, but this is one of the only places in the entire town that has any feeling of hope. Outside it is the same old story everyday. More migrants arrive, and find a nice place on the ground to call their home, the police come, take them away, and then the cycle simply starts again. Here at the center there is a feeling of momentum towards a better future. The adults are learning what their options are, and their kids are playing with each other as if nothing profound was happening in their lives.

Only a few minutes later I was back at the street corner of our house to find that my friend from Delhi was once again standing in front of the corner mart. It had been a few days since I had seen him last, and I had no idea if he had already started heading north.

“How are you?”

“I’m doing well, how are you Bryce?”

“Very well, when are you going to head north?”

“I leave in two days. I will be going to Mexico City where I will stay for a little while.”

“Good luck on the trip. We will be back in Mexico City pretty soon, so maybe we can find a way to meet up there.”

“That sounds good. Do you have Facebook?”

“Of course,” I tell him as I hand him my phone, so he can look himself up. “Send me a message, and when I get there I will try to go on Facebook. I hope you make it alright. We are leaving tomorrow morning, so I don’t know if we will catch you before we go. If we don’t see each other again then I wish you luck.”

“Thank you, and hopefully in Mexico City we can see each other.”

With that I returned to our current home, and spent the remaining time in the city sitting on the patio. A few hours past, and the rain started once again like a monsoon out of nowhere. Up on the roof next door a group of migrants were sitting around completely unmoved by the sudden rain. It was the first time I think I really enjoyed a rain since arriving. I no longer felt the need to fill up the buckets to be able to take a shower. I only felt an overwhelming sense of relief that our experience here was almost complete.

The next morning it was time for us to leave, but in a much different way than everyone else. The bus station was strangely empty considering the hundreds of people that were probably leaving Tapachula that same day. Besides us there were maybe two more well kept families waiting for the 11 o’clock bus to San Cristobal.

The road out seems completely different from the road in. Just 20 minutes into the drive, and we reach our first security point surrounded by national police clutching assault rifles. The driver stops right next to a middle aged officer who immediately jumps on. He gives a sort of fake smile that you expect to see on the face of someone who is trying to coerce you. He then promptly explains in Spanish that they need to check our papers. His sweep through the back of the bus is pretty quick, then he stops at us, and asks to see our documents.

We casually hand over a US and Spanish passport with entrance stamps from four months ago. He immediately raises his eyebrows, and the questions start. He must know what we are doing there, why we would come to Tapachula, and the conditions that brought us to Mexico. It is a brief little exchange, but it is enough to reinforce my happiness to be leaving.

As we pull away I grab a quick picture of the government agents standing in front of the bus. I wonder what they think of all of this. After all, they are just a cog in the machine. Standing on the side of the road in the heat all day without much to do. It’s probably a pretty boring job, but I am sure they feel very important for doing it.

After another thirty minutes or so we come across our next checkpoint, and the same process starts again. At this point the majority of the bus, including Anna had fallen asleep. Everyone was quickly shaken awake as the authorities made another inspection of the bus. This time Anna looked out the window, and very excitedly grabbed my arm as she pointed at the checkpoint, but just as quickly stopped talking as she saw the guard get on the bus.

“I’ll tell you later” she whispered to me as the guard passed down the aisle.

I took a moment to observe where we were, and I noticed an open space below a small aluminum building on stilts on the right side of the road. The whole area was surrounded by tall fences with large rolls of barbed wire crowning the top. The left side of the road had an old official checkpoint station similar to a toll both. The whole checkpoint appeared to have grown out of a simpler time across the road and into a monument to the current crisis.

On second glance I notice some more details of the building on the right. It is completely built out of metal with a number of concrete stilts holding it in place without a single window. The metal stairs that lead up from the ground level ended at a heavy looking door closed tightly with a large padlock. The building itself was incredibly shabby. It was like it had been built as a temporary outpost, but someone forgot it was supposed to be temporary.

As we start pulling away Anna finally feels comfortable enough to tell me what she wanted to tell me when we had first pulled up to the outpost. She points directly at the small building and tells me that it was where they had been holding those 50 Cuban refugees. 50 people complained about their conditions. Instead of receiving sympathy; they are moved to a small metal building without a single window in 40 degree centigrade weather with 90% humidity.

“The only reason they ever got out was because the human rights organization got word that they were there.”

“How long were they there again?”

“About 2 months. The room is big enough for about 4 people, and when the human rights group got them out there were about 30 people staying there. They say that at most they were keeping about 60 people there.”

“Why were they put there?”

“They were all Cubans, and when the conditions at the detention center were really bad they complained a lot. A lot of people from Central America will not say much when they are treated poorly. The Cubans are different. When the police locked up all of the Cubans they just said ‘What are you talking about?’, and they all tried to get out. The police really can’t stand the Cubans. When they lock up Central Americans most of them just let it happen, but Cubans are much more aware of their rights. They demand to have their rights, so when they started to complain about their conditions the police put them there.”

“How did they get out?”

“Someone tipped off the organization that they were there, so they started working with their lawyers to get them out. It took them a while, but eventually they got them out.”

“All because they wanted better conditions?”

“Yep. It all happened simply because they would not do what they were told.”

Another hour passed without anything too exciting happening, and everyone dozed off once again until we made it to our next stop. This time everything seemed much more serious. The bus pulled off the highway into what seemed like a normal rest step, but filled with military. A third officer gets on the bus. He quickly explains that we were going to all have to get off the bus, with all of our belongings. Then we had to grab our bags from the bottom, and make our way into the building. Off the bus we can see that the military is already hard at work inspecting the undercarriage of the bus trying to find hidden migrants, or drugs.

Once we get inside the building we find that they have built something in line with a US airport, or Chinese subway security system along the highway. There are large scanners where we put all of our luggage, passport controls, and armed guards everywhere. More questions, and more suspicious looks from everyone. Then finally we make our way through the other side where the bus is waiting for us to load back in, and get on our way.

After that last checkpoint we are finally on our way. No more questions, no more passport controls, and no more military. Back to reality for at least a little while longer.

Everything that is happening there already seems so distant, so impossible, but it is the reality for everyone there. For most of us, we live in a world where the modern systems of globalization have eliminated the majority of the real struggles that humanity has had to historically deal with. Just about anything we could want is within a click of a button. Global capitalism has without a doubt improved the lives of billions of people. From Australia, Asia, Europe, to North America, we all live in the most prosperous nations and period of humanity.

Conversely we have the many nations around the world that are playing catch up. We look upon them, and wonder when they are going to share in our wealth. We are almost ready to leave them behind again, as the world enters the next series of automation revolutions. With those changes once again possible upon the backs of the developing world.

Things are different now though. Three hundred years ago when the industrial and liberal revolutions took hold, what happened in far off countries didn’t really matter to people in Western Europe. Today a disease can start in Africa, and within days it will arrive on the shores of the United States. Just as a biological disease can spread around the world, so can a social disease.

When we started on our current path of globalization we never really thought about the negatives that could come back to us. We never put systems into place that could help mitigate the potential downsides that would come, but now it’s too late. We cannot go back to our pre globalized world without widespread catastrophe, especially with the problems we have in front of us.

The world has become so interconnected that what is happening here is going to have a rippling effect. The solutions to this problem is hard. The solutions are institutional, and they are unlikely to show themselves until we have reached the brink of disaster. As long as this remains easy to ignore then the solution will be postponed. The real question is how long will we be able to ignore this sad reality as it spreads to more and more people?

These refugees are in a number of months taking a migratory path that took their ancestors hundreds of generations. Long before the idea of the nation state, the city state, or even civilization there was open land, and free movement to every corner of this planet. It was then when their ancestors hailed on lands that are now considered far more important to allow them to stand again. However, the developed world will not be able to hold back the mobs of displaced that are coming in the future. One way or another the walls will be torn down, people will come, and those that have benefited the most from the labours of the developing world will no longer be able to ignore the people they have left behind.

Sources and Other Resources

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees – Women on the Run

This report is where to start when trying to understand what is happening to women traveling through Central America. This is one of the most comprehensive, and insightful reports on the subject. Everyone who is concerned about what is happening should start by reading this report.

United Nations University – Fleeing to Mexico for Safety: The Perilous Journey for Migrant Women

This report contains facts about the reality of migrant women coming from Central America. It includes statistics on the amount of crime they are subjected to.

School of Law, University of Washington – MEXICO’S MISSED OPPORTUNITIES TO PROTECT IRREGULAR WOMEN TRANSMIGRANTS: APPLYING A GENDER LENS TO MIGRATION LAW REFORM

This report contains a lot of information about the recent history of Central American migration. It includes detailed statistics about kidnappings, and the amount of crime migrants are subjected to.

Migration Policy Institute – Women Migrants in Transit and Detention in Mexico

Older report, but still relevant. Contains information about Mexico detention centers with a specific focus on the female populations within those centers.

Washington Office on Latin America – Mexico Now Detains More Central American Migrants than the United States

This is a great resource about increases in detainments as well as information about asylum acceptance as of 2008.

Instituto Para Las Mujeres en la Migración – Acuerdan OSC y Segob instalar mesas de trabajo para atender migración

This article contains information about the lack of understanding migrants have of their rights, and efforts that the human rights organizations have made to work with the Mexican government in order to fix this issue.

La Jornada – Estación del INM en Tapachula es una prisión, se quejan cubanos

This is a detailed article of exactly what happened to the Cuban migrants who were locked up for 45 days in the security checkpoint.

Global Detention Project – Mexico Immigration Detention

This site consolidates information on detention around the world. On this page it specifically highlights the structure and history of Mexican law on the topic of immigration, and how the laws in their current structure leave open the possibility of indefinite detention.

El Heraldo de México – Nueva Caravana Migrante avanza por México tras dos meses varados

This article was written when a caravan of 1,200 entered Tapachula on March 22nd. It details the conditions these people were in, demographics of the caravan, and it is also the source of the image of the migrants in the main square.

POSTA – Migrantes centroamericanos salen de Tapachula

More information about the caravan from the previous article. This article was written in regards to the day they left. It contains some direct details of the hospitality they received from the citizens of Tapachula straight from one of the caravan leaders.

South China Morning Post – As Trump targets China in trade war, Chinese companies could find an ally in Mexico

This article comes from one of the more prominent newspapers from Hong Kong. It contains an interesting perspective about the current trade war, and how it may end up enticing Chinese companies to begin focusing more on tighter relations with Mexico as both Mexico and China become increasingly unable to rely on the United States. The image of the migrants waiting at the human rights center is from this article.

The Economist – The world’s most dangerous cities

This infographic, referenced above, is a comprehensive visualization of the current state of the crime rates within the world.

El Souvenir – La ruta de La Bestia, un viaje que tú también puedes hacer sin tren

This is a great article about the rouse of La Bestía. Our image of the people sitting on the train comes from this article.

Public Radio International – Migrants describe overcrowded Mexican detention centers as Trump ratchets up pressure

Detailed accounts of current conditions at Mexican migration centers, including published statistics of current overcrowding rates.

SDP Noticias – Migrantes pasaron la noche en Tapachula

A brief little article about the migrants sleeping within the main page. This article is where the image of the migrants sleeping in the square comes from.

Institutional Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México – “Jardín y palacio [de] Tapachula” vista parcial

Mexican national archive of anthropology, which contains historical images of many different parts of Mexico. This is the source of the old image of the center of Tapachula.

Detecther – Is Caste System part of Hindu Religion?

Article detailing the efforts to remove the caste system from everyday life in India with detailed information about how it still affects India.

TRT World – Mexico publishes Trump’s ‘secret deal’ on migration

Article with detailed information about the result of the recent deal between Mexico and the United States, as well as the results it has had in Mexico.

Informador – Entra en operación la Guardia Nacional en Chiapas

A quick article about the influx of military into Chiapas.

Subscribe

Subscribe to the Notes From Around The World mailing list, so that you can receive an update whenever a new article is published.